By Greg Bunce on Jun 26, 2017

Rethinking Geocoders: Adding Local Vernacular into the Build Process

This article will take 4 minutes to read

AGRC has been working on a project to enhance our approach to geocoding. This grew from the basic idea that humans often view addressing differently than a GIS system. For instance, as GIS professionals, we are accustom to storing data in a format that is versatile and verbose. The choices we make in maintaining road and address GIS data do not always result in satisfying address geocoding results, especially when best practices don’t accommodate the local vernacular for addressing. A current project at AGRC, code-named Road Grinder, attempts to bridge this gap.

It is common practice in a GIS system to err on the side of including prefix directions for address point and road centerline layers. Yet, it might be more common for prefix directions to be omitted when addresses are used in conversation or supplied on a paper or digital form. An example of this would be Eastwood Elementary School. Eastwood Elementary is located at 3305 Wasatch Drive in Salt Lake City. Note the omission of prefix direction. In a GIS system, data referencing this location would be stored as 3305 S Wasatch Drive. But the geocoder, based on the underlying map reference data, is expecting the input address to contain the valid prefix direction. When a prefix direction is not supplied, a match score less than 100 is generated. The less-than perfect match score can erode confidence in the geocoding-service result, which might require additional manual inspection, or, if left unchanged diminish confidence in results.

This is extremely common for ‘alpha-named’ roads (i.e. streets without grid names like 400 South) throughout Utah. And, what’s worse, public safety address users prefer the additional information while, often the US Postal Service strips it out of their standardized mailing addresses (because it’s unnecessary info within the specified zip code, we think). It is also very common to have entire roads exists in one address quadrant. McClelland Street in the Salt Lake City address system only exists in the southeast quadrant. Addresses assigned to this street in Salt Lake City must have a “South” prefix direction. Locally, “South” can be omitted when referring to addresses on McClelland Street. The same person might add in the prefix for one situation but omit it for another.

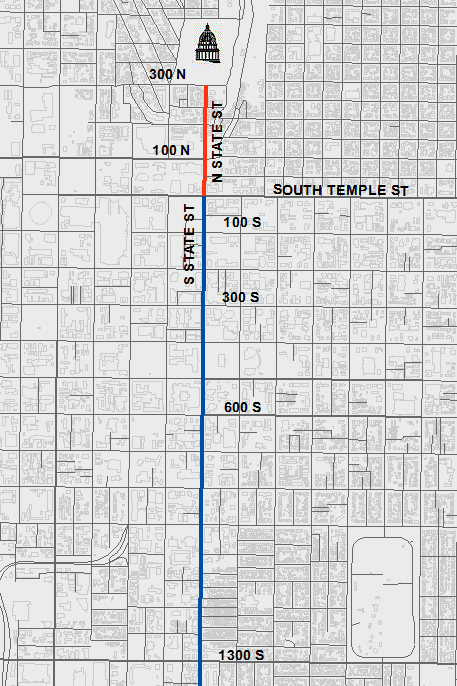

A similar situation occurs on State Street in Salt Lake City.

This image illustrates how only a small segment of this road has “North” addressing. The map shows that the majority of the addressing on State Street in Salt Lake City to be in the southeast address quadrant. It is unnecessary to provide a prefix direction for a house number greater than 300 on State Street. This is why it is just fine to say 1575 State Street in Salt Lake City. Our current geocoding services, however, are expecting the “South” in order to give a match score of 100. This situation is, of course, not unique to State Street.

This image illustrates how only a small segment of this road has “North” addressing. The map shows that the majority of the addressing on State Street in Salt Lake City to be in the southeast address quadrant. It is unnecessary to provide a prefix direction for a house number greater than 300 on State Street. This is why it is just fine to say 1575 State Street in Salt Lake City. Our current geocoding services, however, are expecting the “South” in order to give a match score of 100. This situation is, of course, not unique to State Street.

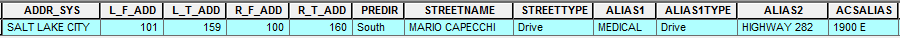

Another challenge to building geocoders is the fact that we often assign a variety of names to the same road segment. Diagram 2 illustrates this well showing how Mario Capecchi Drive is also known as Medical Drive, Highway 282, and S 1900 E. We expect our geocoding services to find a match when given any of the assigned names. To account for this, you could build a geocoder for each alias field in your data. You then create a composite geocoder that links all the contributing geocoders together. In the case of AGRC’s current geocoding service, we have a component service for the all four fields - primary name, alias1 name, alias2 name, and address coordinate name.

Functionally this works fine, an errs on the side of finding the best definitive match, but the searching process can be slow due to the numerous geocoding services that could be called.

So how are we ‘addressing’ these common geocoding situations and also building a better geocoding experience? After a few discussions, we decided to rethink the underlying data. We determined it would be best to create a derivative set of address data that is specific for the geocoders. We automated a process to format the road and address data so that it better represents the range of ways that common addresses are communicated or supplied.

To remedy the often unnecessary expectation for a prefix directions, we programmatically analyzed every address point and road centerline in the State, checking to see if it remained unique when the prefix direction was removed. If the addresses remained unique, they are added accordingly in a ‘alternate names table’ of accepted aliases. The end result will be the ability to definitively geocode addresses with or without a prefix direction. For example you will now get a ‘100’ match score when geocoding 3305 Wasatch Drive or 3305 S Wasatch Drive. Likewise for 1575 State Street and 1575 S State Street.

We have thrown all of the road name aliases into the same alternate names relational table. This eliminates the need for us to build and maintain four separate geocoders and a composite geocoder. This equates to faster, more efficient geocoding for addresses that didn’t match perfectly against the older, more rigid geocoding implementation. And it positions our reference data to be much more inline with the NG 911 GIS data standards that are being finalized by the National Emergency Number Association (NENA).

When implementation is complete (in the coming weeks), we expect our geocoding services to be more versatile, faster, and with higher match scores. We hope this enhances end-user happiness, and, as always we’ll look forward to hearing any feedback you can pass along.

Download the geocoding data here and build your own geocoders.

Visit our GitHub repository to view or contribute to this project.