By Greg Bunce on Mar 11, 2019

The Western Grid, Explained

This article will take 8 minutes to read

Have you ever wondered why the patterns of development in the Western United States are so orthogonal (i.e., “right-angled”)?

Pan around a map and you’ll see the confines of the grid just about everywhere. Grid-like development is nothing new — it can be traced back to early developments in the Middle East. But, why is it so prevalent in the West?

It turns out this gridiron pattern is connected to a 17th-century mathematician, the Treaty of Paris, and Thomas Jefferson. Yup, there’s definitely a connection here, which also helps explain the West’s notoriously wide streets and big city blocks, as well as our nation’s entangled dependence on feet, yards, and miles (i.e., the United States customary units). Read on and we will explore the Western Grid more.

The Survey Chain

Let’s start with the previously mentioned 17th-century mathematician: Edmund Gunter. Gunter was not just a mathematician; he was also an English clergyman, a geometer, and an astronomer. He made several contributions to society, but we’re going to focus on his invention of the Gunter Chain in 1620 (Fig 2).

The Gunter Chain, which was used for surveying, was quickly adopted as a statutory measurement in England and in the British Empire. What made it so popular was its ease of measuring and surveying plots of land for legal purposes. The Gunter Chain measures 66 feet in length and contains 100 links, making it very portable and convenient when working with English units. Measuring an acre (a standard British parcel) was as easy as laying out 10 square chains. When working with smaller plots of land, you’d simply divide the links by 100,000 to get the acres. Additionally, a statute mile was 80 chains.

Because of its ease in calculations, the Gunter Chain was quickly adopted and became widely used for surveying and land management records. In fact, it was so popular that it made its way across the Atlantic with the early colonists. The acre, noted in the Articles of Confederation (1781), was declared the standard unit of land measurement for the new nation. The Gunter Chain made a huge impact when it was developed, and we can still see its lasting effect as we begin to look closer at the western United States grid.

Standard Units of Measure (The Acre)

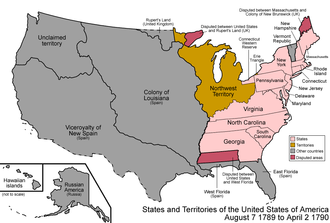

Okay, let’s jump ahead to 1783 and the Treaty of Paris. At this point in American history, the thirteen original colonies had just pulled off the seemingly impossible and defeated the British Empire, ending its colonial rule. This treaty marked the official end of the Revolutionary War and the beginning of independent American governance. In addition to the thirteen colonies, a large swath of land, referred to as the Northwestern Territory (Fig 3), was ceded to the United States. This was good news for a new nation carrying a sizable amount of wartime debt. Fortunately, the largely uninhabited Northwest Territory could be divided and sold off in sections (parcels) to generate revenue for the new nation. Though, first, this land had to be surveyed.

The early American Congress further solidified the acre as the official unit of land measurement with the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the resulting Northwest Ordinance of 1787. These ordinances provided the framework for public lands and the procedures for organizing territorial lands west of the Appalachian Mountains.

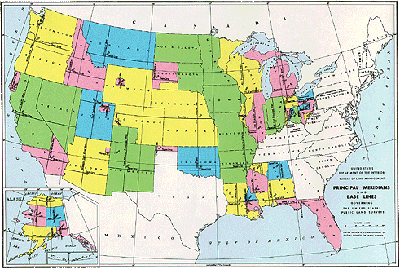

Public Land Survey System

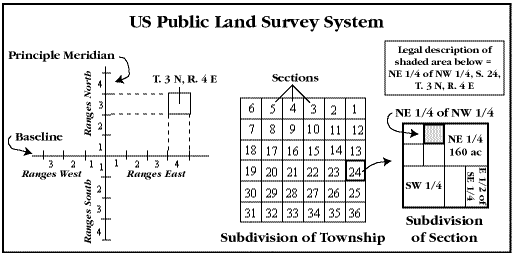

I know, I know… that was probably more history than you were looking for, but really, that’s the annotated crash course for understanding the basis of the present-day Public Land Survey System (PLSS) (Fig 4). This system was originally proposed by Thomas Jefferson and was mandated by Congress to oversee the cadastral surveys of the public lands. Essentially, it was set up to facilitate the transfer of federal lands to private citizens. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is the official record keeper of the surveys. Over the past 200 years, almost 1.5 billion acres have been surveyed into townships (and ranges) and sections. These surveys were conducted primarily west of the original thirteen colonies and north of Texas (Texas has Spanish roots and Spanish land grants). Presently, areas of Alaska are still being surveyed.

As with any measuring system, you need a starting point. Within each PLSS system, this is where a defined meridian line (north-south) meets a defined base line (east-west). Most of Utah is within the Salt Lake Meridian PLSS system for which the base and meridian intersection point is at Main Street and South Temple in downtown SLC (Fig 5). A small portion of NE Utah is governed by the Uintah Special Meridian which is its own separate PLSS system whose base and meridian lines intersect in the city of Roosevelt. All official surveys in Utah have an underlying reference to one of these two points. In other words, every township and section in Utah is numbered off of these locations. Other PLSS states have their own unique meridians (Fig 4).

Townships are made up of thirty-six square miles, with each square mile known as a section. Sections are eventually subdivided down to an acre by way of half sections, quarter sections, quarter-quarter sections, etc. (Fig 6). An acre, again, is simply 10 square chains, and there are 640 acres in a section (a square-mile) or 40 acres in a quarter-quarter section. Hence the phrase, “40 acres and mule” is all you needed to be self-sufficient.

No matter how you shake it, though, land measurements in the West are consistently divisible by the magic 66-foot Gunter Chain. You’ll see its effect everywhere. This measuring unit was so successful because it made the math easy — and many early surveyors had a shaky grasp of mathematics and they were required to work quickly.

These early surveyors typically placed a permanent monument at section and quarter-section corners. These markers are still heavily used today and are the starting point for almost every Western legal description you’ll encounter, including land deeds (the transfer of private property), water rights (well locations), and taxing areas, as well as municipal annexations and, consequently, voting districts. Because of this, it has been difficult for the US to adopt the International System of Units (the modern metric system).

It is precisely this survey pattern that explains why the western United States is so orthogonal. Although the grid is not unique to the West, it’s certainly at the core of all land sales and, as a result, it influences many development patterns. Let’s look at a few examples.

The Western Grid

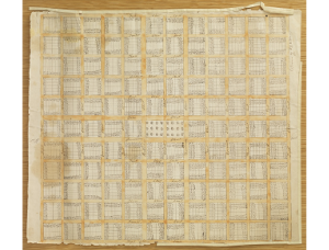

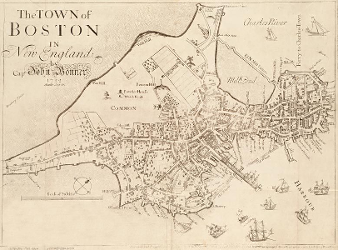

One of the more dominant patterns you’ll see in the West is the rectangular city block. You could argue that the Mormon pioneers helped carry this development pattern west from Missouri with their Plat of Zion (Fig 7) and their subsequent establishment of more than 700 communities. Contrast this pattern with the pre-PLSS pattern of the early colonial settlers in Boston (Fig 8).

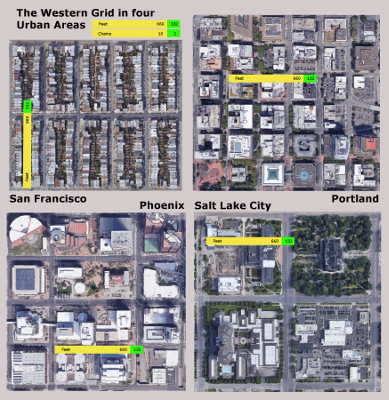

Large city blocks are a common theme in the West. They typically vary between 198 feet, 330 feet, and 660 feet (which is 3, 5, and 10 chains). Often, two sides of the block are 660 feet, with the adjacent sides being 198 feet or 330 feet. Looking at Portland (Fig 9), their blocks are unusually small for the West at 198 feet x 198 feet. On the other side of the spectrum, Salt Lake City (Fig 9) is known for having the largest blocks in the West at 660 feet x 660 feet. Blocks are more rectangular in San Francisco (Fig 9) and Phoenix (Fig 9), as they measure 660 feet x 198 feet and 660 feet x 330 feet, respectively.

If you have ever tried to cross the street in downtown Salt Lake City, you know our intersections are extremely wide. You’ll see the Gunter Chain’s lasting mark at these intersections as well. Looking at Portland (Fig 9) and Salt Lake City (Fig 9) again, you’ll notice two variations of the chain. Salt Lake City (Fig 9) has large intersections that are based on two chain lengths (132 feet), whereas in Portland and San Francisco intersections measure half a chain (33’). In Phoenix (Fig 9), you’ll notice intersections measure one full chain length (66 feet).

Section Lines and Addressing

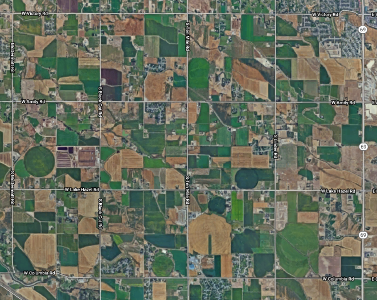

Another notable mention are “section line roads.” These roads are laid out in a one-mile by one-mile grid pattern that follows the section lines. Figure 10 shows a good example of this southwest of Boise, Idaho. This pattern is also very popular in Phoenix and Las Vegas.

Section lines in North Dakota and South Dakota are often used as the basis for their street numbering systems. In Salt Lake City, a similar section-based addressing system is used, where the 100 blocks (e.g., from 100 E to 200 E) are ten chains, or 660 feet, or quarter-quarter-quarter sections (10 chains or 660 feet).

One last notable Western development pattern is the disguised grid. These are often large communities where the land is typically purchased by the section (or more) and then is made to feel less grid-like. Two good examples of this pattern are Sun Lakes (Fig 11) and Sun City in Arizona. As you move through these communities, you forget that you’re on the grid.

It’s remarkable how a few key points in history have permanently affected the growth and development patterns in the western United States. It’s also interesting how these same decisions have made it difficult for us to turn our backs on the imperial-based measurement system (i.e., United States customary units).

So, the next time you’re out wandering the Western Grid and you encounter a large intersection or a big city block, you can think back to Edmund Gunter, the Treaty of Paris, and Thomas Jefferson.

-

American Publishing Company, “Salt Lake City 1891 Bird’s Eye View,” Historic Map Works, Residential Genealogy, accessed March 1, 2019. http://www.historicmapworks.com. ↩

-

“Gunter Chain,” (image) John Johnson (owner), Smithsonian National Museum of American History, accessed March 01, 2019. http://americanhistory.si.edu. ↩

-

Golbez, “States and Territories of the United States of America August 7 1789 to April 2 1790,” Wikipedia, “Northwest Territory” page, accessed March 1, 2019. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Northwest_Territory. ↩

-

United States Bureau of Land Management, “Principal Meridians and Base Lines,” US Geological Survey, updated January 18, 2018, accessed March 01, 2019. https://nationalmap.gov/small_scale/a_plss.html. ↩

-

“Great Salt Lake Meridian/Base Marker,” HowderFamily.com, updated August 13, 2013, accessed March 01, 2019. https://www.howderfamily.com/travel/utah/great-salt-lake-base-and-meridian.html. ↩

-

“US Public Land Survey System,” (image), San Francisco Estuary Institute & The Aquatic Science Center, accessed March 01, 2019. https://www.sfei.org/it/gis/map-interpretation/projections-and-survey-systems#sthash.D2D94lF3.sWlKZBU3.dpbs. ↩

-

Frederick G. Williams, “Revised Plat of the City of Zion, Circa Early August 1833,” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, The Joseph Smith Papers, updated September 01, 2018, accessed March 01, 2019. https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/revised-plat-of-the-city-of-zion-circa-early-august-1833/1. ↩

-

John Bonner, ca. 1643-1726; William Price, fl. 1725-1769; and Francis Dewing, fl. 1716-1722, “The town of Boston in New England,” Map, 1723, Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, accessed March 01, 2019. https://collections.leventhalmap.org. ↩

-

Greg Bunce, “Variations on the Western Urban Grid,” Automated Geographic Reference Center, March 01, 2019. ↩

-

Google Maps, “Boise Idaho,” accessed March 01, 2019. https://google.com/maps/place/Boise,+ID/. ↩

-

Google Maps, “Sun Lakes, Arizona,” accessed March 01, 2019. https://google.com/maps/place/Sun+Lakes,+AZ. ↩